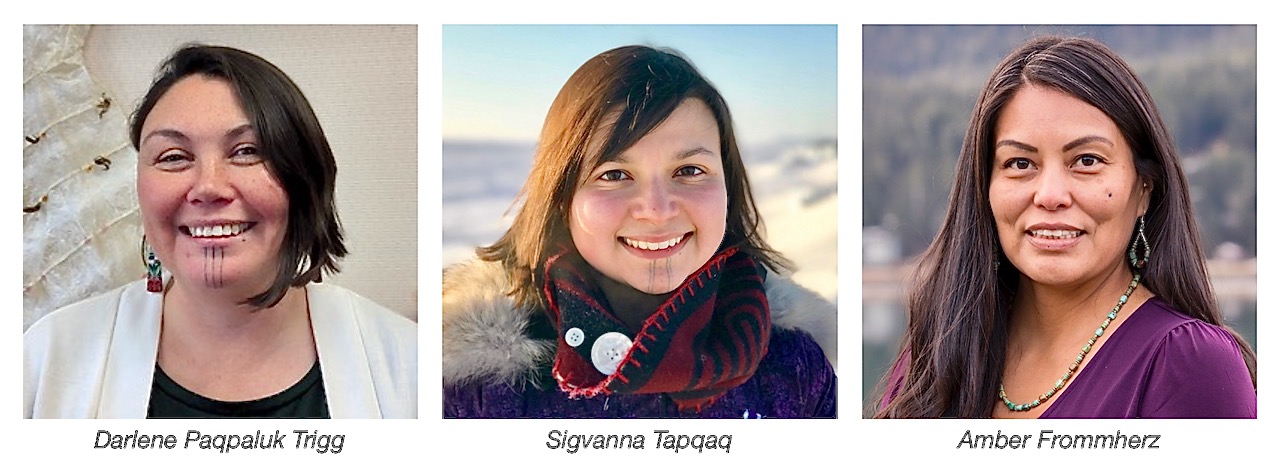

Darlene Paqpaluk Trigg – AASB Board of Directors, Nome Public Schools School Board

Sigvanna Tapqaq – Nome Public Schools School Board

Amber Frommherz – AASB Board of Directors, Juneau Borough School Board

Submitted on behalf of the AASB Board of Directors’ Ad Hoc Committee on Tribal Consultation and Tribal Compacting

In Alaska, where more than 200 federally recognized Tribes steward lands, languages, and cultures thousands of years old, the education of Native children cannot be approached as a neutral or disconnected task. Our schools exist on Indigenous homelands. Every classroom, playground, and school board meeting takes place in a space shaped by Tribal histories and living cultures. Recognizing this, federal law requires school districts receiving Title program funds—such as Title VI (Indian Education), Title I (academic achievement), and others—to engage in meaningful consultation with Tribes.

But for Alaska, this is not just a compliance checkbox. Done well, Tribal consultation is an act of relationship-building that strengthens educational outcomes and advances equity. It is a practice grounded in respect, reciprocity, and a shared vision for the success of Native students—and indeed, for all students.

Legal Responsibility and Moral Imperative

Under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), districts receiving significant federal funds must consult with local Tribal officials and parents of Native children when developing plans for using those funds. This is particularly relevant in Alaska, where many school districts serve predominantly Alaska Native communities.

The legal requirement exists to ensure that decisions about funding—whether for academic support, language programs, cultural enrichment, or student wellness—reflect the priorities of the communities those funds are meant to serve. But in Indigenous worldviews, obligations to each other extend far beyond statutory language. Consultation is not just about “checking in” on plans already made; it is about co-creating those plans from the ground up.

In Alaska Native cultures, decisions that affect the community are guided by strong value systems passed down for millennia that inform how to be good, relational human beings. In Iñupiaq communities, for example, guidance for decisions that shape our children’s future flows from our ilitqusiat—”the things that make us who we are.” At the heart of these values is piqpaksriḷiq iḷiḷgaanik—love for children—joined by others such as kamaksriłiq utuqqunaanik (respect for Elders), aatchuqtuutiliq avatmun (sharing), savaqatigiiyułiq (cooperation), and kamakkutiłiq (respect for others).

Applied to education, these values invite us to ask:

- Are we rooted in love for children, nurturing their well-being, language, spirit, and cultural identity?

- Do our systems reflect and uphold our ilitqusiat worldview, shaped by collective care, respect, and reciprocity?

- Are we centering the wisdom of our Elders and community bearers as we make decisions for our young ones?

These are the lenses through which districts must enter consultation—ensuring that every choice is grounded in love, respect, and the enduring spirit of our ilitqusiat.

Moving Beyond Procedural Compliance

Too often, “consultation” risks becoming a once-a-year meeting with a pre-written agenda and little space for true dialogue. An Indigenous lens reframes consultation as an ongoing, respectful conversation rooted in mutual accountability.

True consultation means:

- Early Engagement: Inviting Tribes into the conversation before decisions are finalized, so their perspectives shape priorities from the start.

- Two-Way Communication: Creating space for Tribal leaders, Elders, and families to share their knowledge and aspirations—and ensuring that districts respond in meaningful, documented ways.

- Cultural Safety: Holding meetings in environments where Native participants feel respected, heard, and understood, and where Indigenous knowledge is valued as equally authoritative as academic research.

- Follow-Through: Demonstrating, in action and budget, that Tribal recommendations are not only heard but integrated into final plans.

This approach honors Indigenous self-determination, a principle affirmed in federal Indian law and in the lived experience of Alaska’s Tribal governments.

Benefits to Districts

When districts engage in authentic Tribal consultation, the benefits flow in both directions.

1. More Relevant, Effective Programs

Tribal leaders and Native educators bring expertise in culturally responsive teaching, language revitalization, and community-based learning. Integrating this knowledge makes programs more engaging and relevant for Native students, leading to better attendance, stronger achievement, and improved graduation rates. These gains strengthen the district’s performance overall.

2. Stronger Community Trust

In Alaska, where the history of education includes the trauma of boarding schools and the suppression of Native languages, trust between schools and Tribal communities must be intentionally rebuilt. Meaningful consultation signals respect for Tribal authority and a willingness to repair and strengthen relationships.

3. Compliance and Funding Stability

From a practical standpoint, meeting and exceeding federal consultation requirements protects districts from compliance findings that could jeopardize funding. But more importantly, it ensures those funds are spent in ways that have the greatest positive impact on student success.

4. Richer Learning for All Students

Culturally grounded curricula developed in partnership with Tribes benefit Native and non-Native students alike. Learning local history from the perspective of the people who lived it, hearing Indigenous languages in the classroom, and participating in cultural activities fosters mutual respect, empathy, and civic awareness.

An Indigenous Framework for Consultation

Indigenous frameworks for governance and education are not linear; they are relational. In Yup’ik, there is a teaching that “We are bound together like the strands of a net.” Each knot is a relationship, each strand a responsibility. In the context of school districts and Tribes, this means that educational planning must be woven together with cultural knowledge, community priorities, and the lived realities of students’ families.

Practical steps for districts adopting this lens include:

- Establishing standing advisory committees with Tribal representation.

- Co-hosting community forums in partnership with Tribal governments.

- Incorporating Elders and culture bearers into classrooms, not as guests but as co-educators.

- Providing training for district staff on the history, rights, and contemporary realities of Alaska Native peoples.

- Evaluating program outcomes with both Western metrics and community-defined indicators of success, such as language fluency, cultural pride, and student well-being.

Conclusion: From Obligation to Opportunity

For Alaska’s school districts, Tribal consultation for Title funds is more than a mandate—it is an opportunity to transform the relationship between schools and the Indigenous communities they serve. It is a chance to repair historical harm, honor Tribal sovereignty, and co-create educational experiences that affirm the identities of Native students while enriching the learning environment for all.

When approached with humility, curiosity, and a commitment to reciprocity, consultation becomes a living expression of partnership. It ensures that every dollar spent under Title programs reflects not only federal priorities but also the voices, visions, and values of Alaska’s first peoples.

In doing so, we honor both the letter and the spirit of the law—and most importantly, we honor the children whose futures depend on the strength of the net we weave together.