Māori Immersion Schools Model Possibilities for Alaska

By Tiffany Jackson, AASB Board President

When is the last time you went on a trip that was truly life changing? The kind of life-changing which has you looking at everything you do, and thinking about how your new view on things is prompting you to consider changes to what you’ve always done. At the end of February, as a part of the Robert Wood Johnson Global Solutions Partnership, 12 Alaskans from different aspects of education (principals, teachers, school board members, AASB staff) had the opportunity to go one of these life-changing trips to Aotearoa (New Zealand).

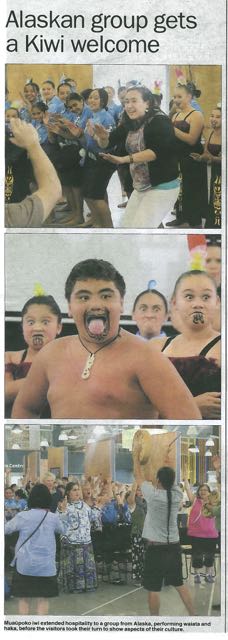

Story from the Horowhenua Chronicle about the Alaska delegation’s visit to Levin, New Zealand. (click on article to read full screen)

I was curious as to how this trip would impact our work in public education. It was clear from the beginning; all of us would be changed by our experience. “This exchange will have a greater impact than any other type of communication” shared Marie Tozier, “We were immersed in the possibilities as well as the Māori language and culture.”

The hosts extended traditional hospitality to the Alaska delegation, who in return shared Alaska Native cultural greetings. (click on article to read full screen)

It was evening when we arrived. We were greeted by representatives of the iwi (tribe) through a traditional pōwhiri (welcoming ceremony). From this initial welcome, through the whole trip, we had experience after experience of hearing people speaking to us in Maori, unapologetically, knowing we couldn’t understand what they were saying, but firm in knowing it is important for them to speak their language.

Helen Gregorio, Southwest Region School Board Member, reflected on how powerful it was, and how it made her think about our own elders. How many times do we have English speaking representatives come to our villages, and speak to the community, and how often do we have elders not really following what they’re saying? Here we were, feeling completely welcomed as visitors, but also somewhat like outsiders as we weren’t sure what was being said.

From early morning to late night, the Alaska delegates were hosted for a large part of our time in Aotearoa by the Muaūpoko iwi (tribe) at their Marae. From being hosted in a single room Marae to eating their traditional foods, to being shown how they’re addressing indigenous education in Aotearoa we were treated like extended whānau or family.

We were also fortunate to have Watson Ohia, a superprincipal, escorting us to the various schools, and speaking on our behalf during the pōwhiri or welcoming ceremony held at each school. Mr. Ohia eloquently shared with us, the model they were implementing for the Māori students within the various school types. At the core of this successful educational movement, was the idea that education should be designed “For us, by us, our way.”

The full immersion into the Māori culture radiated through everyone. “Seeing Māori kids who were culturally grounded in who they were was POWERFUL” shared Kiminaq Maddy Alvanna Stimpfle, a second-grade teacher in Nome. “This trip has really inspired me to continue to follow my dreams of teaching holistically with instruction all in Inupiaq, grounding students in their cultural identity.”

The students of Manukura (high school) in Palmerston North perform haka during the pōhiri (traditional welcome).

Ultimately, at the core, the Māori Education model is ancestrally driven, but future focused. School boards and policies ensure that each student’s education has meaning and links to the student’s plans well beyond graduation. This partnership between families, community organizations, and the schools is working, with 91% meeting national certification. The Kura schools are now the highest performing schools in the country, while successfully integrating Māori culture and language into the curriculum and developing leadership skills in their students.

Māori language instructional materials used in immersion schools.

There are striking differences between the models of education we saw in Aotearoa and what we have in Alaska. The Māori have local control over their curricula in order to meet their demanding national standards. Their local boards control what their graduation profile looks like, and what they want their students to have learned and achieved when they graduate. Unlike many of our graduation requirements, these graduation profiles want their students to achieve more than straight academics; they want their students to be well-rounded people who contribute to their community in meaningful ways and are deeply connected to their culture. The partnerships, place-based learning, infusion of tribal values all play a large part of their educational structure. They work at helping students identify how being Māori is relevant in the world at large. This, in particular, struck me when thinking about how we struggle in Alaska as well, how is being Alaska Native relevant in the world at large? How can Alaska Native values help all students succeed in education and life?

Māori art at the entrance of the Westpac Stadium in Wellington. The “Tiki Māori” is a human form.

At times, it was overwhelming to think, this system is so different, how could we possibly take what we’ve seen and learned here, and apply it to the system in Alaska which is so different. However, we were reminded day after day, the Māori system didn’t always exist as we saw it in February.

The first school we visited started with just two students, and two days before it was set to open its doors, it was informed by the government it hadn’t been registered as a school. The leadership decided to capitalize on this and simply not call itself a school initially so it could be free of some of the regulations mainstream schools had. It was later after it had demonstrated success with its students when it finally became recognized as a school. They don’t want to be doing the same thing in 10 years that they’re doing today, because that would be an indication they’ve become stagnant.

WestPac Stadium in Wellington, New Zealand – Te Matatini Kapa Haka festival biennial, organized to foster, develop and protect traditional Māori performing arts.

Principal Hami shared that in addition to the school’s focus on literacy, numeracy, they included a focus on ‘culturacy’ to build competence and knowledge in their cultures. All of the Māori educators and partners encouraged us not to wait for the system to catch up; it will always be behind the movement. Real systematic change can start with just one person with the drive and desire to make a difference “The trip has opened my eyes to see, that all I really need to do is just start” shared Kiminaq Maddy Alvanna Stimpfle.

Ultimately, this trip has profoundly impacted 12 Alaskans and our work in education. Marie Tozier from the Northwest Campus of the University of Alaska Fairbanks shared, “Spending time, food, and location with the Māori will help us to remember what we are striving for when we have to work with people who may not be ready for change.” In a period in Alaska’s history which is fraught with so much uncertainty, this experience has given us hope, and inspired the drive to make the systematic changes Alaska needs to best serve our students.

# # #